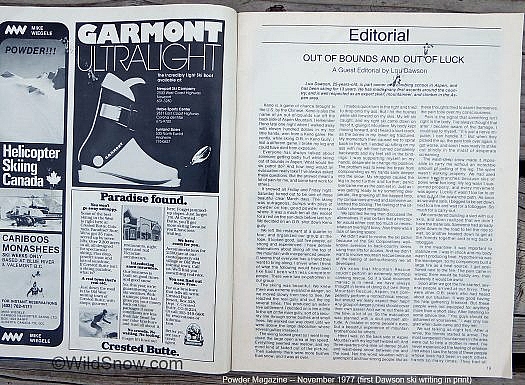

OUT OF BOUNDS AND OUT OF LUCK — Powder Magazine Guest Editorial – November 1977

The article below is lightly edited from the original, with modern commentary in [square brackets]. Please note the bulk of the article was first published in 1977 and will read somewhat dated — as well as embarrassingly sophomoric. We keep it published for cultural and historical perspective, as well as the timeless lessons it teaches us.

Please note: I used these writings as the inspiration for a chapter in my memoir, Avalanche Dreams. The memories I relate in the memoir differ slightly from those below, due to the refinement of time as well as many conversations with others who were there.

Keno is a game of chance brought to the U.S. by the Chinese. Keno is also the name of an out-of-bounds (O.B.) backcountry skiing run off the backside of Aspen Mountain — Aspen Colorado’s signature ski hill. I remember Reno, Nevada late one night when I walked away with eleven hundred dollars in my hot little hands, won from a Keno game. Recently, while skiing O.B. in Keno Gully I lost a different game. I severely broke my left leg and could have died from exposure or medical complications.

Aspen’s backcountry ski community has always talked about someone getting badly hurt while skiing out of bounds in Aspen. What would the ski patrol do? And how long would an evacuation really take? Little did I know the person we asked those questions about would be me.

It snowed all day Friday and through Friday night. Saturday turned out to be one of those beautiful clear March days. The skiing was outrageous, bumps with piles of soft snow on top, good powder everywhere. It was crazy mach-ten all day except for a rest at the Sun Deck restaurant before last run. We decided on the O.B. shot down Keno gully.

We left the restaurant at quarter till four and organized our group at the rope. It looked good, just five people, all strong and experienced. We were under-equipped however, with little more than the items we skied with in the resort. No packs or shovels, just the clothing on our backs. As poorly prepared as we were, I shiver when I think of what the following would have been like with less competent companions. There were two former ski patrolmen in our group.

The skiing was beautiful. Tasty March fluff. We knew the avalanche danger was extreme, so we skied one-at-a-time from tree to tree. We reached the real gully and ski cut the top several times. This produced an extensive settlement. I decided on a line a little to the left of the main gully, sort of a security line through some bushes and small trees. We worked our way down until we were above the large avalanche deposition area where several gullies intersect.

The skiing looked great below so I went firing down the large open area at top speed. Everything seemed mellow and my mind faded out of the picture as I clocked off high speed turns. Then suddenly there were more bushes than snow, and it was all over.

I made a quick turn to the right and tried to drop onto my ass. But I hit the bushes while still forward on my skis. My left ski caught, and my right ski came down on top of it, gluing it into place. My body kept moving forward but my randonnnee bindings didn’t release.

[In 1977, any randonnee binding you could get had compromised safety release compared to alpine bindings. In this case I was on Ramer bindings, but it could have been any such binding.]

I heard a loud CRACK as the bones in my lower leg fractured. My momentum then caused me to spiral back to the left. I ended up sitting on my butt with my left foot turned completely backwards and my feet still in my bindings. I was supporting myself on my hands, desperate to change position as the pain was intense. The problem was to keep razor sharp broken bone ends from punching through the thin skin of my leg as I sank deeper in the snow below my hands. My struggles caused the leg to bend farther and farther; panic overcame me. Just as I was getting ready to try something desperate, like gnawing off the trapped limb, my companions arrived and someone unlatched the binding.

The relief was intense. But my foot was still turned around backwards and causing intense pain. More, if left that way the circulation could be impaired and I could loose the foot. Kendal, one of the former patrollers who was along, applied traction and twisted my foot back to the correct position — as I screamed in pain.

After that I was still hurting and in shock, but I switched from panic to survival mode.

We splinted the leg then discussed alternatives. Our location wasn’t the worst you could imagine, but it was bad. We were still about a thousand vertical feet above the valley floor, with the exit route below us blocked by thick brush, steep gullies and deep unconsolidated snow. We considered requesting a helicopter, but figured it would cost to much or only come in the morning, necessitating an overnight stay.

[No kidding, I was laying there severely injured and was worried about the cost of a helicopter that actually would have been free.]

Also, we weren’t sure a helicopter could get close enough to extricate me from the brush thicket in the narrow gully.

We were loath to involve the ski patrol because of the Ski Corporation’s well known aversion to backcountry skiers using their lifts for access. And we didn’t want to involve mountain rescue because we’d developed a strong culture of self-sufficiency in our group, and frankly, we were blinded by pride.

[It’s embarrassing how disconnected we were with the local mountain rescue volunteers, that we didn’t trust them and implement a rescue immediately. But the mountaineering culture of Aspen in the 1970s was very different than today — closed ski area boundaries didn’t help with that.]

Our attitude about Mountain Rescue Aspen (MRA) did have some basis in reality. While MRA could do competent hike and helicopter style missions, they couldn’t perform extremely technical climbing rescues, thus local technical climbers such as our group didn’t feel connected with them. As a result we’d always thought in terms of self sufficiency. A noble attitude in some ways but more than a little impractical in real life, as we’d soon find out.

So, our attitude about getting rescued was to wonder if we really should expect MRA’s help, e.g., any group of danger junkies should cover their own asses! And we’re out there all the time around here, a lot of us, so we’ve got the manpower.

Thus we planned my evacuation with this crazy do-it-yourself attitude and wouldn’t notify the authorities till much later that evening. A mistake in some people’s eyes [including my own 30 years later], but what turned out to be a beautiful experience of mountain brotherhood.

Here I was, in the middle of the backcountry on the side of Aspen Mountain, with my leg half twisted off. And three-quarters-of-a-mile of mountainside, dense brush and waist-deep snow between me and the road. Not the worst situation with a good splint and four strong people, or so we were thinking. But as these thoughts tried to assert themselves pain took over my consciousness and I ceased taking much more part in the rescue than that of being a shock addled victim.

Pain signals something isn’t right in the body. I’ve always thought that after I became of aware of the damage from an injury, I could say to myself, “it’s just a nerve impulse, I can handle it.” But when my friends picked me up and tried to move me (It was necessary for us to move out of the middle of the avalanche path, in case a slide triggered), the pain took over. It got worse, and I soon I was ready to strike out blindly in the midst of desperate screaming.

The waist-deep snow made it impossible to carry me without an incredible amount of jostling of the leg. Our splint didn’t work. We’d used some crooked tree branches, and my leg wasn’t supported properly. Every movement was agony. Luckily it wasn’t too far to an area out of the avalanche path. As soon as we were safe I begged to be set down next to a fire and wait for rescue that would hopefully be something like a patrol toboggan. So much for our noble plans of self sufficient carry-out. But we kept working from the point of view that we could do this with the local mountaineering community and not involve Mountain Rescue.

PART TWO — The Rescue, and an Analysis

We considered building a sled with our skis, and soon realized we didn’t have the materials to do so. Someone had already gone down to the road to tell the ride we’d arranged to wait (as if the guys would just carry me down there in 10 minutes). So another headed down the hill to get the community together and bring back a toboggan. This would set several processes in motion.

In the meantime it was important to stabilize me. I was in shock and my body wasn’t producing heat. Hypothermia was the immediate danger, so my companions built a large fire as a heat source. I got positioned next to the fire. The pain came in waves — there would be hardly any then suddenly it would be awful — nearly unbearable.

Soon after we got the fire started several people arrived at our bivvy after climbing up from the road. They were other O.B. skiers who had heard about our situation. It was good having the help gathering firewood, but these guys were not equipped for anything more than a short stay. More, their advice was limited to comments like, “you guys should be ashamed of yourselves.” I was glad when dusk came and they left.

We sat talking as night fell. After a while the friends started to arrive. The most competent mountaineers in the area were out to help a brother in need. I’d never experienced the emotions I felt when I saw the faces of people who’s lives had been in each others hands so many times. They had all dropped what they were doing to help a friend.

After exchanging greetings and socializing for a while (if you can call it that, as I lay there shivering in a haze of pain), we heard the sound of a snowmobile in the valley below. We assumed people had obtained a rescue sled and they were bringing it as far as they could get with a snowmachine. We were also surprised to hear yodels coming from the top of the gully.

In forty-five minutes a group of people arrived with a rescue sled. The had driven the snowmobile part way up the exit trail, then muscled this huge sled up the gully to our location. The sled looked good, but I started to dread the trip down because of my terrible splint.

We heard more yells coming from up the gully. It was certain someone was coming down from the ski area. At that point we’d realized that a totally improvised rescue was going to be an ordeal, so we hoped they people coming down might have a good splint and perhaps even a patrol toboggan, though we couldn’t imagine how they’d get a sled down Keno gully.

While we were speculating, a friend arrived with morphine. The doctor who worked with Mtn. Rescue had given him this manna, and his skills as a former ‘Nam medic came in handy when he cut through my ski pants and jabbed the needle in. The relief was intense.

The folks coming down arrived. It was Harvey Carter, ski patrolman, and climbing mentor throughout my days as a novice alpinist. I’d been feuding with Harvey of late because he’d gone off on me for doing the first free ascent of a rock climbing route he’d made claim to. He’d actually gotten violent, and I feared he was going to beat the tar out of me someday. I looked up in his face and said something like, “Wow, it’s good to see you, are you still mad at me?” His answer was something along the lines of a gruff but obviously caring, “Nope, let’s get you out of here Louie.”

Everyone was impressed with Harvey bringing the sled because we knew how steep the upper part of Keno gully was. “It got in front of me a few times,” was all he said when asked what it was like bringing a rig down Keno. Harvey was known as one of the toughest patrollers and a local iron man alpinist, and his bringing that rig down Keno is now a local legend in certain circles, and something for which I’m forever grateful.

It wasn’t hard to decide which sled to use. After being properly splinted we began the trip down. The terrain was extremely difficult — endless dense brush with intense drop offs that Harvey would launch like something out of a movie stunt sequence. I remember the constant sound of branches scraping the sled cover above my face. At least 50 people were scattered over the length of the trail, and it was all hands on task as the sled moved though the terrain. After two hours of grueling work the procession arrived at the snowmobile, and soon after I was shanked into the waiting ambulance and whisked away to the hospital, where the news was bad, but I was glad to hear it.

Analysis (1977)

What comes to mind most often is how responsible I am for what happened to me. I don’t blame the bindings, or the snowpack, or the brush. If I’d been skiing like the competent mountaineer I supposedly am and less like a ya-hoo, I wouldn’t have been hurt. And that’s the basic rule of backcountry skiing that I broke; ski like you’ll never get out alive if you get hurt. More, remember that being a good skier doesn’t make you invulnerable.

I frequently think of how close I came to really eating it. What if we hadn’t had any matches? What if I’d done something like broken a femur, or my neck? What if it had been twenty-degrees colder and snowing? Or how about if I’d been O.B. skiing alone — something I did on occasion?

The answer to all those questions is that O.B. skiing with nothing but the clothes on your back is probably the most dangerous thing you’ll ever do. Just think about it.

I know that I’ll always ski in the backcountry. And I feel everyone has the right to use ski lifts for access to the backcountry near our ski mountains. But the safety situation in Aspen is not as it should be. Some of the risk should be eliminated.

We need a sign-out system, preferably through the ski patrol. This would serve to eliminate rescue time lag, as well as enhancement of communication with the ski patrol. The ski patrol wouldn’t necessarily perform O.B rescues. Perhaps we could form a subsidiary mountain rescue group, specifically for O.B. skiers in need.

[Note, no cell phones back in 1977, they’re now frequently used by Aspen backcountry skiers needing help.]

The thoughts above are nice, but reality is different. I’ve talked with people who work for the Ski Corporation, and it sounds like a clandestine relationship with a few patrolmen is the only thing possible at this time. I’m thinking now that an organization of backcountry skiers is the best alternative. We could operate our own sign-out system. And perhaps, some day, the Ski Corp will give more support to the mountaineering spirit of Aspen.

Another thing and O.B. skiers’ organization could do would be to put in a few strategically located rescue caches. The caches would primarily be first aid and survival gear. Their purpose being to help stabilize a victim until the rescue is complete.

All these things involve some complex organization. But the most important thing is the easiest to handle and the lesson I learned in Keno Gully. That’s simply that everyone who goes into the backcountry should be equipped to insure the survival of a hurt and immobilized skier. It just has to do with a little personal responsibility.

[Notes from Lou: I tried to leave the immature and idealistic tone intact, while editing the article a bit from the original so it’s a better read. It was funny to see the pre cell phone communication ideas. Also amusing is how backcountry out of the Aspen ski areas is now a tacitly sanctioned activity and has little to none of the issues we were dealing with in 1977. Things have indeed changed for the better, but people still go out unprepared and some pay the price. We never got any sort of real backcountry skier’s advocacy group formed in Colorado, about the only thing that’s happened in that area is the formation of the Backcountry Skiers Alliance, and they’re mostly interested in restricting mechanized recreation. Around the state (and country) backcountry skiers are constantly dealing with access issues caused by ski resorts, private land and even endangered species. We still need an organization that speaks for us. Perhaps, some day…

I still see Harvey Carter every few years. He’s quite old but still active and the last I heard even doing some rock climbing! Tough guy, and that proves it. The memory of Harvey looking down at me when he arrived at our bivvy is one of my most cherished and sweet from four decades of alpinism. It wraps up everything good about alpine brotherhood; forgiveness, teamwork, sacrifice for others, all supported by athletic and technical excellence. Thanks Harvey.

(Harvey Carter passed away in 2012).