Lou’s News #4 — Grooming Granite

Greetings all. After years of blogging at WildSnow.com, I have no trouble spitting out text. That’s great when you post shortform four or five days a week. But shift the venue to a stack of words stuffed between two covers, and the ability to flow—or better put—to flood, can bite you. It did me.

My coming memoir (on tap for winter 2023-24) has been a five-year battle between my keyboard and my page-count limit. And there’s no clear winner. Along the way, vignettes fall like autumn leaves because they’re redundant, or too hard to research, or just too weird. Or simply because there’s no room, not enough paper and ink, not enough spine width. Yet the tales live on my hard drive, and some shall see the sun. Here’s one, pumped up a bit for your email reading pleasure.

* * * *

GROOMING GRANITE

by Lou Dawson

1973. Aspen climbers such as Steve Shea, Larry Bruce, Michael Kennedy, and me yours truly were emigrating to Yosemite Valley every spring and fall. But the short, intense Independence Pass cliffs remained our home turf, a few miles east of town, up quaint, 2-lane Highway 82.

Indy was storied climber Harvey T. Carter’s home as well. In fact, he’d put up most of the first ascents. If you called the place “Harvey’s Cliffs” rather than Independence Pass, you would not be far off the mark.

Now in his mid-forties, Harvey was old school to us twenty-somethings. Yet he was still finding new routes, and he was a mentor for some of us—for Michael and me.

I won’t dig into Harvey’s pedigree. Just know he’s an icon of Colorado and Utah climbing history. You can find his story in books such as Desert Towers by Crusher Bartlett, and Climb! by Achey, Chelton, and Godfrey.

Yet there’s a part of his story the books gloss over. It’s not exactly pedigree. Kind of the opposite, actually.

Along with Harvey’s devotion to (make that “worship of”– some say that before his death in 2012 he’d ticked over 5,000) firsts, he liked to improve things. In my estimation, during his days on the crags he often spent as much time “gardening” as he did climbing. Sometimes more. If a tree obstructed a climb, or was growing roots that might fracture the cliff, Harvey hiked up there with his chainsaw and excised it. Likewise, loose rock was trundled. Public land? National Forest? Bah.

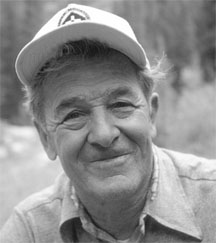

(Below: Harvey T. Carter in his later years; he didn’t look much different in his forties. Overall, he was a tough guy, a scraper, but with a heart—and he did enjoy improving those cliffs! Photo: (c)Cameron Burns.)

Because of Harvey’s self-elected public service, the areas below the Indy cliffs often resembled an artillery shredded no-man’s-land. Denuded trees, turned-up soil, maybe even the flinty smell of nuked granite if the gardener had visited recently.

Despite the aesthetic carnage, my climbing partners and I liked the concept: safer, better! So our own climbs often included a dose of tilling—a rock here, a stone there. I never packed a chainsaw, but many branches succumbed to the tiny, razor-sharp saw that folded from my Swiss Army knife. For me, the process had the same creative appeal as finding new climbing routes, but with much less commitment. It could also be fun, provided you ignored the fact that heaving rocks down mountainsides was a climber taboo. With good reason.

* * *

It was one of those perfect pre-autumn days you get at moderate altitude in Colorado. Maybe seventy degrees, aspens beginning to color, bluebird sky you knew would last into the evening. A perfect day for Independence Pass.

Around noon, Michael Kennedy and I headed up to Indy for a climb on Weller Slab, a pale granite cliff about 400 yards above Weller Campground. We parked in the only vacant campsite, then hiked north toward the cliff on a climber’s path through thick aspens. Near the cliff base, we wove through a field of jumbled boulders, pried from the wall above by powers of nature: freeze-thaw; glaciers; Harvey Carter’s biceps.

The first part of our route led to a comfortable ledge. Break time. We tied into the wall and rested with our legs dangling over the edge.

The campground was less than a quarter-mile below us. Children’s laughter drifted on a light breeze; a counterpoint to our high heroics. No one had noticed us, or they had and quickly lost interest in a couple of slow-moving climbers — like watching paint dry.

Ten minutes later, we traversed the ledge to start the next pitch and passed through a sort of tunnel behind a large boulder. Similar in shape to an oversized mattress, it was about eight feet high and four feet thick. A big chunk of stone; maybe 28,000 pounds, the mass of four full-size pickup trucks. Channeling Harvey, I braced one hand against the cliff and pushed the other against the boulder, imitating Hercules busting his chains. The rock moved an inch and made a grating noise. Somehow, despite resting for millennia, it teetered on its balance point.

“We should knock this thing off,” I said. “That’ll make things safer, this ledge nicer. We always clean what we can… Like Harvey does.”

We paired up behind the boulder, backs to the cliff, and pushed with our feet, like we were doing squats. We soon had the big stone rocking like a boat. Then, on a count of three, with one final and mighty thrust, the pressure on our feet released like magic. Fourteen tons of crystallized magma tilted over-center and flew, bouncing off a series of ledges, exuding a cacophony of liberation that easily matched the sonic booms of a Memorial Day military flyover.

As the stone slammed the boulder field, Michael blurted, “Will it stop?”

It did not stop.

In mounting horror, we watched our proud trundle ricochet from the boulder field, take a hundred yards of the air, and hit the aspen forest like a lawn mower from hell.

The racket was beyond belief: harsh blasts of stone-on-stone punctuated by the crackle of rending wood as aspen after aspen splintered in the path of destruction, their shattered stems falling towards the campground like medieval lances.

The campers dropped their spatulas and forks. This was not drying paint. Death was on the wing.

Accompanied by a final symphony of crunching, thumping granite, the boulder came to rest in the trees a few hundred feet from a tent. Paralyzed by the horror of potential manslaughter and fearing we’d be identified as the cause of a near catastrophe, Michael and I cowered behind a small tree on our ledge.

The spectators below sprang to action. Tents came down, hot dogs and burgers were returned to camp coolers, car doors slammed.

After the exodus, a half-dozen campers remained. We heard them shouting to each other across the campground’s asphalt circle.

“You think we should leave? How big was that? Dangerous!”

“I don’t think so. I don’t hear anything else up there. I don’t want to hassle with packing up; we’re in the middle of our picnic!”

Nothing like a cozy fire and half-cooked s’more to gentle the prospect of death.

Expecting a Forest Service ranger or sheriff’s deputy to arrive any minute, Michael and I tiptoed from the cliff and skulked into the aspen forest. We hid our climbing gear in my backpack, circled the campground so we’d walk in from the direction of the road, then ducked into Michael’s car and made our getaway.

That afternoon I stopped by Harvey’s house. “We cleaned a big one off Weller,” I gushed. “It knocked down trees, almost took out the campground.”

“I’ve got a pry bar for the next one you do,” Harvey said as he rubbed his hands together, like he expected a delicious meal.

-end

(Note from Lou: The practice of extreme gardening fell out of favor as climbers focused on the (now) cleaner cliffs of the Pass, and environmental awareness increased. Errant stones—what’s left of them, anyway—are still trundled, but only when absolutely necessary. Also, a disclaimer: Please know this is narrative nonfiction; it reflects my memories and is not intended as written history.)